It was a rushing, a burning, an all-things-are-change, a compulsion.

I was torn up for three days or was it two weeks, except the long moments when I just forgot. Intertially, suddenly remembering, half weeping, half positively reconstructing my own construction of who I am and why.

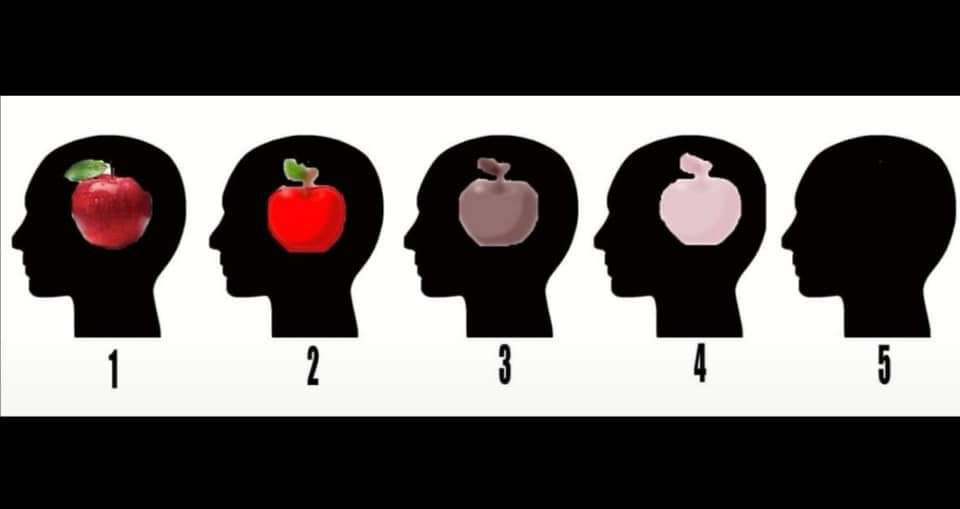

Everyone I talked to I would grill – wait, what do the sheep look like when you try to go to sleep by counting them? And when you read a book, how good quality are the faces of the people you imagine?

Everyone is blind-sided. Either grilling me back for hours trying to understand how I do anything without a mind’s eye. Or kind of bland to it, so not used to describing their inner lived experience, they’ll say what it is, but not quite get just how much it varies between people.

The one commonality – everyone, everyone having previously assumed that we all perceived / absorbed / processed, that our internal phenomenology of being a mind was the same.

It’s not.

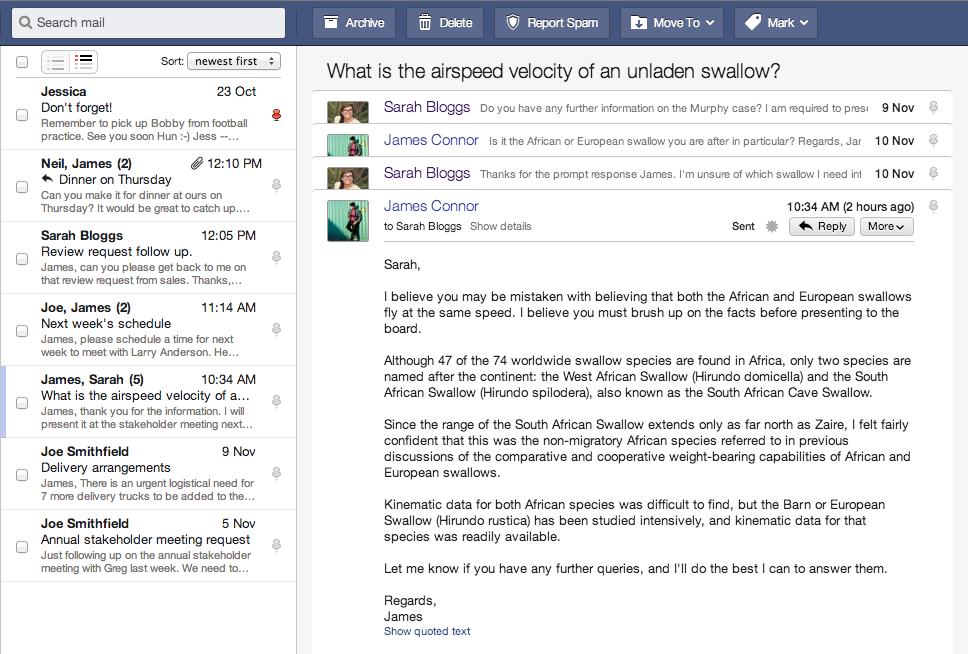

A rush of others in the same situation as me pour through the aphantasia subreddit – “without imagination”, a word only coined, literally a concept only known in 2015, just six years ago. You can read the FAQ which has links to tests to take to help you understand what’s going on.

Or you can just ask everyone. Grill them. Compel them.

Think of an apple, what colour is it?

When you dream are the images like an old black and white TV, like just a sense of emotion and relation, or like a 4K film?

If you imagine a future event do you play it out as a video, do you see it from a first person or a third person, how long is the film, how does the camera move?

Can you voluntarily hallucinate a dragon coming out of the pavement in your main perceived world? (Warning note: This is unusual, and not being able to do this does not mean you’re aphantasic. Some people can do it, it’s called prophantasia)

When you recall a traumatic experience does it literally flash back as an image of the scene into your mind, and what’s that like – maybe a gif, what quality, how long, or do you just remember the feeling of pain?

If you’re navigating round a city, do you look at the map and remember it and bring it up on your second screen as you need it? Or do you remember the street you’re in and quickly fast forward along it to see what is ahead? Or do you orient the spatial elements without any vision? Or do you just have no idea, do you just get lost?

Just go, find a housemate or a random stranger outside a coffee shop or your closest love, go ask them.

I’ll be here writing about six more blog posts about this, I haven’t begun.